Universal nasal spray vaccine protects mice from multiple respiratory pathogens

Summary

A nasal spray vaccine tested in mice activates the innate immune system, providing months of broad protection against various respiratory viruses, bacteria, and allergens. If effective in humans, it could become a universal seasonal vaccine.

A universal vaccine protects mice from multiple pathogens

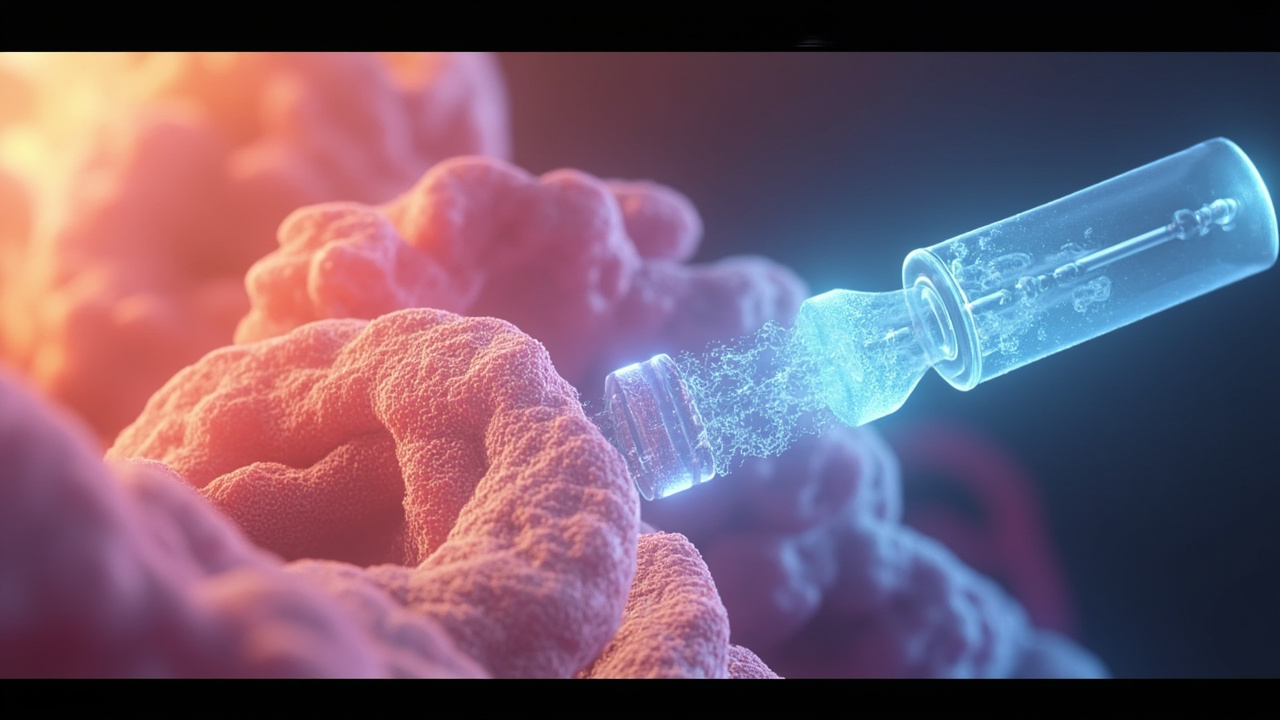

Researchers have developed a nasal spray vaccine that protected mice from a wide range of respiratory viruses, bacteria, and even allergens. The study, published today in Science, suggests a path toward a universal respiratory vaccine for humans.

If successfully translated, such a vaccine could be administered seasonally to guard against flu, COVID-19, and other threats. It could also serve as a first-line defense against future pandemics.

How the vaccine works by activating the innate immune system

The vaccine, developed by a team led by Stanford immunologist Bali Pulendran, takes a novel approach. Instead of targeting the adaptive immune system—which learns to recognize specific pathogens—it broadly activates the body's faster, more general innate immune defenses.

This system includes cells like macrophages that reside in the lungs. The team previously studied the BCG vaccine, which offers temporary, non-specific protection by similarly activating innate immunity.

The new vaccine has three key components:

- Two drugs that stimulate receptor proteins to activate innate immune cells.

- A third component with an immunogenic protein from chicken eggs that stimulates a population of T cells.

These T cells then send continuous signals to keep the innate immune system in a heightened state of alert. In experiments, immunity quickly waned when the third component was omitted.

Mice showed broad protection for months

In the study, mice received four doses of the nasal vaccine. They were then protected for at least three months against several pathogens.

The protected threats included SARS-CoV-2, other coronaviruses, and bacteria that cause respiratory infections. The vaccine also suppressed the immune response to house dust mites, preventing allergic asthma in the mice.

Pulendran describes the protection as a "two-bulwark system." First, a mucosal barrier in the lungs limits pathogen entry. Second, the primed lung immune system mounts an extraordinarily rapid response to any viruses that slip through.

Experts call the findings exciting and clear

The research has drawn positive reactions from other immunologists not involved in the work. Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at Yale University, called it a "fantastic paper" and said the data look very clear.

"If it works in humans, that would be really quite remarkable," Iwasaki said.

Zhou Xing, an immunologist at McMaster University, noted that the concept builds on advances in mucosal vaccines over the past decade. He referred to the approach as a "bridge vaccine" that leverages the innate immune system for non-selective protection.

The next major step will be testing whether this broad protection can be safely and effectively replicated in human trials.

Related Articles

Stanford scientists develop nasal spray vaccine that protects mice from viruses, bacteria, allergens

Stanford researchers developed a nasal spray vaccine that, in mice, broadly protects against various respiratory viruses, bacteria, and allergens for months by boosting innate immunity. Human trials are next.

Stanford nasal spray vaccine protects against viruses, bacteria in animal tests

Stanford researchers develop a universal nasal spray vaccine, tested in animals, that primes lung immune cells to broadly fight viruses, bacteria, and allergens, marking a radical new approach to immunization.

New mucosal vaccine clears C. diff from gut in animal models

A mucosal vaccine clears C. difficile from the gut, preventing infection and recurrence, unlike traditional systemic vaccines.

Stay in the loop

Get the best AI-curated news delivered to your inbox. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.