Astronomers confirm runaway supermassive black holes traveling at thousands of km/s

Summary

Astronomers have discovered evidence of runaway supermassive black holes, propelled by gravitational wave recoil from collisions, traveling at high speeds through and between galaxies. While one entering our solar system is possible, the odds are extremely low.

Astronomers have discovered runaway black holes

Last year, astronomers spotted a runaway asteroid from another star system moving at 68 kilometers per second. Now, new evidence confirms the existence of something far more extreme: runaway supermassive black holes, traveling at thousands of kilometers per second through other galaxies.

Several papers published in 2025 show images of long, straight streaks of stars within galaxies. These are the predicted "contrails" left behind as a massive black hole tears through interstellar gas, triggering star formation in its wake for tens of millions of years.

The physics of a black hole rocket

The story of how a black hole gets kicked into a runaway trajectory begins with a collision. When two spinning black holes merge, they release immense energy as gravitational waves.

If the spins of the two black holes are aligned in a specific way, this energy is ejected more powerfully in one direction. The newborn black hole recoils in the opposite direction like a rocket.

Supercomputer calculations show this "kick" can propel the black hole at speeds up to thousands of kilometers per second—fast enough to escape its home galaxy entirely.

From theory to detection

This was theoretical until the LIGO and Virgo observatories began detecting gravitational waves from colliding black holes in 2015. Key evidence came from studying the "ringdown," the final ringing signal of the new black hole.

The ringdown reveals the black hole's spin. Observations confirmed that many merging black holes have large spins and randomly oriented axes, the precise conditions needed to create powerful, runaway kicks.

The discovery proved the mechanism was real. A runaway black hole moving at 1% of light speed would travel on a near-straight line, not a curved orbit like a star.

The first direct evidence appears

Finding a relatively small, stellar-mass runaway black hole is difficult. But a supermassive one, with millions of times the sun's mass, leaves an unmistakable trail of destruction.

In 2025, astronomers published images of these trails. A study led by Yale's Pieter van Dokkum described a contrail 200,000 light-years long behind a distant galaxy, imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope.

The data suggests a black hole 10 million times the mass of the sun traveling at nearly 1,000 km/s created it. Another paper describes a 25,000-light-year-long streak across galaxy NGC3627, likely from a 2-million-solar-mass black hole.

What this means for our cosmic neighborhood

The existence of these massive runaways implies smaller ones are also out there. Gravitational wave data shows some mergers have the opposing spins needed for a kick, and the speeds are easily high enough for intergalactic travel.

This introduces a new, dynamic ingredient to our universe: black holes as high-speed intergalactic travelers. It is not impossible, though extremely unlikely, that one could pass through our solar system.

The gravitational disruption from such a visitor would be catastrophic, knocking planets from their orbits. However, the odds are astronomically minuscule.

This discovery doesn't present a new danger. Instead, it makes the story of our universe richer and more exciting than it was before.

Related Articles

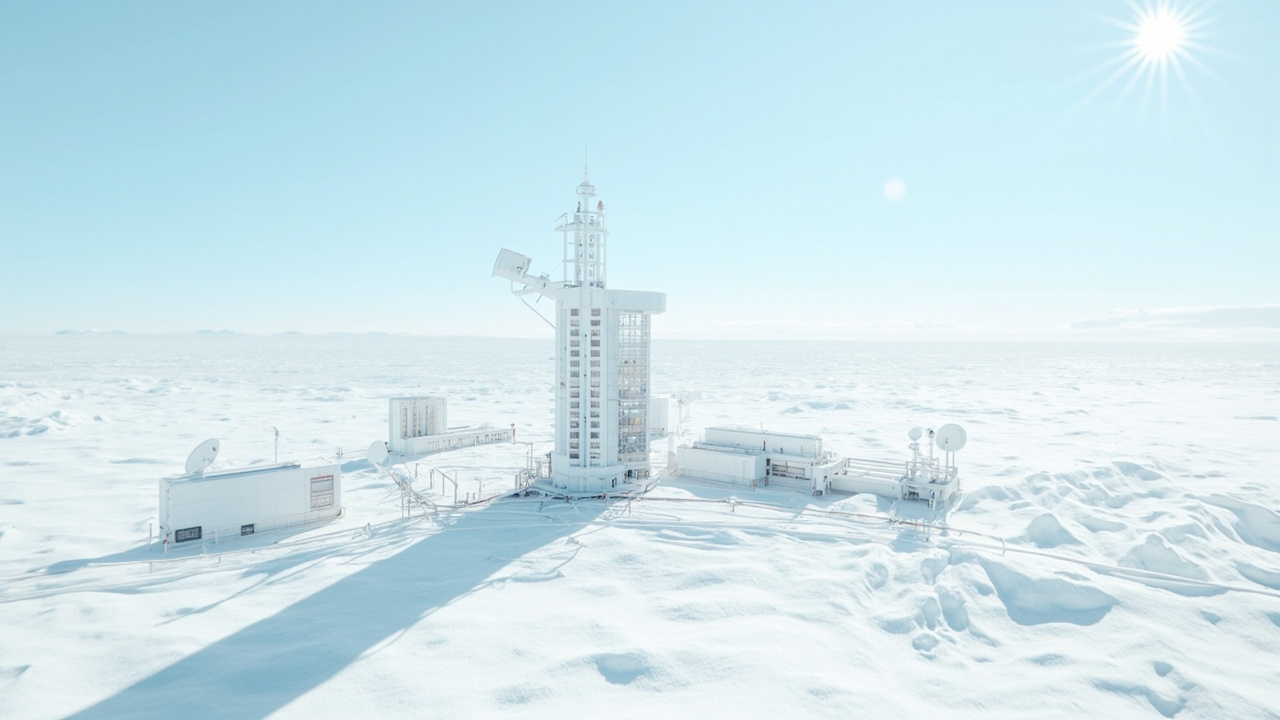

US seeks Greenland military sites for space race advantage

Trump's interest in Greenland centers on its strategic value for Arctic dominance and space operations, particularly the Pituffik Space Base, highlighting tensions in international space and territorial law.

Russian cosmonaut completes spacewalk outside International Space Station

A Russian cosmonaut conducted a spacewalk outside the International Space Station.

Annular solar eclipse creates 'ring of fire' over Antarctica

A "ring of fire" annular solar eclipse occurred over Antarctica on Feb. 17, visible as a partial eclipse in some southern regions.

Stay in the loop

Get the best AI-curated news delivered to your inbox. No spam, unsubscribe anytime.